Review: 'hunger' by Joanna Ward

It’s a pretty rare experience to be able to go to an opera knowing that you’re going to be watching something that is (a) feminist and (b) completely new; Joanna Ward’s hunger, which will be performed at this year’s Edinburgh Fringe, promises to tick both of these boxes. Hunger illustrates an artist’s (Anna-Luise Wagner) attempt to ‘strive for aesthetic beauty every day in her performance of [her] domestic life’ after her decision to have children and partially renounce her successful artistic career. Its strong focus on feminist issues, including the conflict between family and career goals, and the limiting categorisations placed upon ‘women artists’, allow hunger to offer a particularly relevant and compelling perspective on contemporary issues faced by women in the arts.

It’s a pretty rare experience to be able to go to an opera knowing that you’re going to be watching something that is (a) feminist and (b) completely new; Joanna Ward’s hunger, which will be performed at this year’s Edinburgh Fringe, promises to tick both of these boxes. Hunger illustrates an artist’s (Anna-Luise Wagner) attempt to ‘strive for aesthetic beauty every day in her performance of [her] domestic life’ after her decision to have children and partially renounce her successful artistic career. Its strong focus on feminist issues, including the conflict between family and career goals, and the limiting categorisations placed upon ‘women artists’, allow hunger to offer a particularly relevant and compelling perspective on contemporary issues faced by women in the arts.

The narrative, a collaborative effort between Ward and Ryan Hay, provides a perceptive and engaging insight into these issues; rather than offering a black-and-white view, their characterisation allows for a more nuanced approach. The decision to create a female impresario (Eleanor Burke) illustrates how concepts such as ‘sisterhood’ can sometimes fall short. In response to the artist’s rejection of gallery works, she argues that it is better to be a woman artist than no artist at all; the artist, then, has to make the too-common choice between accepting gender stereotypes and categorisations or rejecting such categorisations at the likely expense of her career.

Hunger also illustrates the inescapable conflict likely felt by many women between their personal goals and family lives. While the artist attempts to combine her domestic life and career by turning her house into her artwork, hunger shows how this can go awry. As it progresses, the music and narrative become increasingly unsettling and claustrophobic. A particularly striking moment in the opera is a present-giving scene that starts out as humorous but soon comes to demonstrate the dissatisfaction, and even the distress, felt by the artist towards her family life. Ward’s music creates the growing sense that the artist is trapped by her domestic life and the societal expectations placed upon her. Indeed, the artist seems blocked by obstacles at a number of moments; opening with an all-male chorus of ‘watchers’, who detail the artist’s past successes, creates the impression that we can only step into this woman’s life through this male-dominated frame or barrier. Overall, in its tackling of issues faced by women in the art world, hunger refuses to brush over the very real barriers that are present here. Rather than offering a rose-tinted view of women’s experience in the arts, or an attempt to suggest the existence of a perfect harmony between a career and a family, hunger instead leaves the audience thinking about the realities of these issues, and the obstacles faced by women that, despite claims of gender equality, don’t appear to be going anywhere.

Ward’s music is excellent at portraying hunger’s unsettling, claustrophobic narrative; her setting of the text also proves clear enough to avoid the need for surtitles, while remaining compelling. The cast are highly engaging to watch: Eleanor Burke and Anna-Luise Wagner in particular skilfully portray the tensions inherent in hunger, and the watchers (Louis Watkins, Ruari Paterson-Achenbach and Joe Rooke) offer a humorous, yet often chilling, presence. The orchestra, conducted by Ed Liebrecht, proved similarly skilled, showcasing Ward’s music in the best possible light. Overall, hunger is a well-written, thought-provoking and highly compelling opera; if you’re a fan of feminism/new music/opera/a fun combination of the above, then I would highly recommend a visit to its Fringe performances!

Keep up to date with hunger via Twitter and Instagram @hunger_edfringe and go to their webpage https://www.joannamward.com/hunger-edfringe for more information regarding the Fringe run (4th-11th August at Paradise in the Vault).

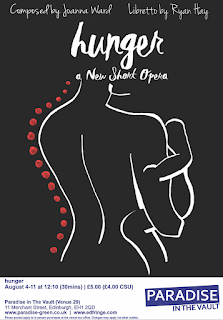

Illustration credit: Bella Dalliston

Illustration credit: Bella Dalliston

Comments

Post a Comment